Felipe Gómez is a journalist with extensive experience working for Chilean newspapers. I met him a few years ago in Bonn, where we were both pursuing different postgraduate programs related to anthropology. We worked together at the Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Bonn, and it was there that I discovered Felipe also has a deep passion for music. He grew up in a family surrounded by music! He plays the guitar regularly and has been immersed in music since childhood, attending the conservatory at the University of Talca alongside his siblings. He studied violin, his older brother studied guitar — who dedicated himself professionally to music, becoming a renowned musicologist — and the youngest played the cello. His background in journalism and his musical abilities converge in his project CHILE PUNK: cartografía del punk chileno (a cartography of Chilean punk), a platform dedicated to promoting the punk scene in Chile. I must admit that punk isn’t a genre I know much about, but my curiosity for learning about projects that blend unfamiliar musical styles and share them through digital media is what led me to interview Felipe. This relaxed interview focuses on that particular project and his career as a communicator.

Chile Punk has been spreading the Chilean punk scene for a while now. What was the initial motivation for creating this platform, and how has it evolved since then?

In 2020, it had been about a year and a half since the social uprising in Chile. I was living in Germany and felt quite useless from a distance. Since moving here, I always had the urge to do something journalistic, which is what I studied, that would connect topics of personal interest: music and politics. All of these interests came together—social, political, journalistic, and musical—and I started sketching what this website could be. At first, I thought of it merely as a website, but I faced a very important issue: logistics. I was far from Chile and was going to discuss events happening there. So, I began reaching out to some people I knew, and that’s how a few collaborators joined the project. A friend of mine, who is a graphic designer, told me, “I can’t actively participate, but I’ll provide you with the virtual space so you don’t have to pay for a server,” for example. Others contributed sporadically at the beginning. That’s mostly how it went. I was consuming a lot of information online about the social uprising when one day, I saw a video that caught my attention. It featured a group of guys playing a Rage Against the Machine cover in Plaza Italia, but they had changed the lyrics. That’s when I realized this was actually what I wanted to do. Logistically, it wasn’t that difficult because I had contacts, etc. The project developed much more later on, but it started as a website aimed at informing and promoting bands while also engaging with what was happening in Chile.

So, you didn’t have a clear plan—you just started and figured things out along the way…

Yes, exactly. I didn’t create a blueprint or anything. I started off with a lot of drive, really, and without overthinking. As I progressed, I started encountering problems and difficulties, and then I figured out how to solve them. However, I didn’t have a specific plan for what I would publish. It was a somewhat vague idea that has taken shape over time—though it’s still a bit formless—but it continues to evolve as time passes.

In today’s independent music context, how do you see the importance of supporting local bands and self-managed projects? What role do you think Chile Punk plays in this dynamic?

Honestly, I don’t believe Chile Punk plays a significant role—it’s a small outlet compared to others that also promote music. I’ve noticed there’s a relatively active ecosystem of self-managed media. For instance, there are some digital fanzines that cover the hardcore scene, like Hardcore Life and Opción de Vida. Additionally, several more well-known outlets cover rock music, including independently produced rock. Therefore, I don’t see Chile Punk as particularly influential—I’m quite realistic about that. Nevertheless, I think it filled a gap that didn’t exist at the time by covering the punk-rock scene in Chile with original content. This means not just copying from other outlets, but providing “journalistic quality” content—generating original material and promoting local bands. The bands themselves have told us that there’s a lack of platforms for exposure—for people who’ve been working for years, who maybe have a couple of demos out, or sometimes an independently produced album, but who aren’t featured in the bigger media outlets, like Rocaxis, for example, which is the major digital platform in Chile covering rock and the underground scene, but with much more well-known bands. So, I think that Chile Punk—as a website, podcast, and on social media—has filled a gap that wasn’t being addressed. That said, there’s still a lot of work to do. Local scenes in Chile are incredibly diverse, and that has also been something the page has gradually discovered over time.

When I was browsing the page, what really caught my attention was how different the musical styles were. I had assumed that, since it was called Chile Punk, the content would mostly be about punk music and maybe a bit of other stuff—but that’s not the case. Why the name? Or did you originally plan to focus on punk and it later diversified as you started discovering new things?

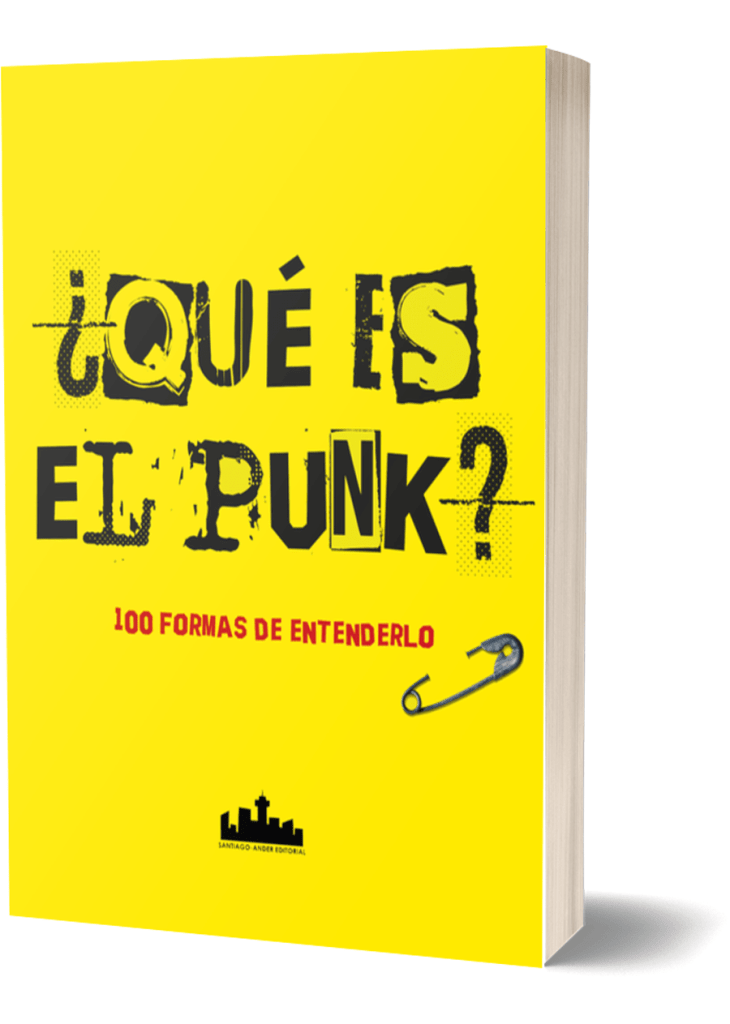

Honestly, I don’t really remember how I came up with that name. I think I toyed with the idea for a few days until I felt it worked. My initial idea was to focus only on punk-rock—where the Chilean scene is small compared to other countries—but in terms of social phenomena, it’s actually quite broad. Every city, even the smallest towns, has a scene. I realized it was much bigger than I had thought. That said, I need to reflect a bit on what I understand punk to be. I could talk about punk as a music genre but also as a way of viewing life. Since I was a teenager—around 15—I began listening to music, going to gigs, and connecting with others in the scene, and I think it’s something that isn’t very clearly defined. A book was recently published by Santiago-Ander featuring 100 people defining what punk is, and everyone offers an interesting perspective on what it means. For me, it’s a way of understanding life. It involves self-management and social relationships—it’s much more than just a music genre. That’s why punk continues to endure, despite some people claiming that “punk died in the ’70s,” and others asserting that “punk is not dead,” etc. This is why new young people keep showing up, along with those who are 50 or 60 years old and still active in the scene—because it’s something really broad. For me, punk is more than a music style. It relates to a way of confronting life, which is reflected musically in the messages that different bands convey. You can hear a hip-hop group with lyrics that could totally be considered punk. There are metal bands with rebellious, political lyrics, too. It goes beyond that—it’s about breaking established norms. You don’t need to have a mohawk or wear studs to feel punk. I feel punk, but I’m not dressed in any specific way. Understanding that punk is a broad concept, a way of viewing life, I believe punk appears in many areas of life. I view it as something that spans different sociocultural strata, and in that sense, I’ve come across many bands that have caught my attention. I’ve discovered a lot of hip-hop artists with very strong lyrics. I really like Portavoz and Subverso, for example—rappers whose lyrics are incredibly powerful, sometimes even more so than some punk bands. For all these reasons, I think the page gradually opened up to other musical styles that also explore this political dimension through music.

When someone who doesn’t know much about music hears the word “punk,” don’t you think the first thing they imagine is the look — spiky hair, studs, chains, black clothes — rather than the actual music style?

Yes, definitely. When I mentioned the Chile Punk project to some people, they’d respond, “Okay, but who’s going to read it? Those punks are just a bunch of drunks…” This creates a caricature of punk as someone who panhandles, drinks boxed wine, and passes out in the street. While those characters do exist, the page is aimed more at individuals who fundamentally approach life from a more critical or oppositional perspective. You can certainly conduct a simple musical analysis of punk, but there are also punk bands that have refined their sound and achieved remarkable things. It’s no longer just about three chords, playing fast, and shouting on stage. Overall, the page caters to people who enjoy reading, discovering new bands, understanding lyrics, and uncovering the meanings behind them. The positive reception the project has received is what has sustained it over time. Additionally, the page has explored various formats like news, interviews, and podcasts.

Which of these formats has received the most and best response from the audience, and why do you think that is?

I believe the podcast has been the best received so far — or at least the one with the most interaction from people. I think podcasting, like radio in the past, is a format that offers a lot of freedom. You can listen without using your hands, allowing you to tune in on the subway, train, or cooking. This freedom makes the content so accessible, which likely explains its positive reception. To better understand how things operate, I installed Google Analytics on the site, learned to use WordPress, and realized that many people read — but don’t spend much time engaging with the content. The internet has conditioned us to consume information quickly. Scrolling through Instagram or TikTok and watching 30-second clips has significantly impacted us. We’ve lost the habit of sitting down and reflecting. Nowadays, artists rarely release full albums; very few produce concept-driven records. We are accustomed to rapid content due to the multitude of stimuli — there’s constant competition for our attention. You pick up your phone, and you’re faced with 10,000 distractions at once. Yet, with a podcast in your ears, you tend to keep listening. This is why I believe podcasts perform better. However, I’ve also noticed that a lot of engagement occurs on social media. The website has a solid audience too, even though I haven’t consistently maintained the level of output I’d prefer. At times, months pass between posts, yet the site continues to prosper — which really surprises me. Approaching the project as a multi-platform effort is intriguing but also quite demanding and challenging because each format requires its own communication style. In summary — to answer the question — the podcast has undeniably been the format that generates the most interaction and interest from people. I’ve adapted to the times… I’m not quite a boomer yet!

Chile Punk has covered major events like concerts and local punk-rock festivals. How do you choose which events to cover, and what criteria do you use to highlight certain bands or artists? How does that selection process work?

Honestly, there are no specific criteria or formal guidelines for that; it’s usually based on what we can manage logistically. If someone is available to attend a show or write a review, we proceed. Regarding band selection, the only real requirement we’ve established is that they have some published material, such as a demo or an album. When I call for submissions, I consistently receive emails from bands working on new projects who send great rehearsal recordings. However, it would be impossible for us to cover every single band out there. Therefore, that small barrier — having something officially released — provides a practical way to determine who we feature. Personally, I find the political dimension of a band important, whether they are punk or from related genres. For instance, there are bands like Los Mox, who are identified as punk-rock, but I’m not interested in covering them because I don’t see any political content there — aside from songs about drinking, which is fine, but it doesn’t align with what Chile Punk is about. That doesn’t undermine the work that the band has done; it’s just not our focus. These are the small criteria we’ve used to select events, and it’s been interesting — sometimes international artists reach out to us. Luciano from Ataque 77, for instance, who left the band and now has his own project, wrote to us recently. The same goes for a former guitarist from Dos Minutos, who is coming to Chile with his project. Sometimes these opportunities come to us without us actively looking, and if we can cover them, we do, and we try to spread the word. A lot of the time, bands send us flyers for gigs and events, and we do our best to share them because everyone mentions the same thing: there is a lack of spaces and platforms for exposure. Independent bands often have to do everything themselves — be their own producers, sound engineers, promoters, and invite everyone — and that’s super hard. That’s why Chile Punk gives space to both established or better-known bands and to new and emerging projects.

How do you see the current state of the Chilean or Latin American punk scene, and what trends or new names are you excited about?

One thing that truly surprises me is that new bands continue to emerge today. In every region of the country, there are fresh bands alongside others that have been well-known for years. I’m amazed that despite all the dominant cultural influences, young people are still getting into this. I believe the scene remains very much alive. Some people define a “scene” as something that exists only when there is a complete infrastructure around it — like venues to perform in, record stores selling music from small bands (I’m not even sure if that still exists), and so forth. However, I would not define a scene in that manner. To me, it’s more about the ongoing activity of making music. By that standard, I believe the scene is thriving — it’s truly fascinating. One thing that stood out to me was how many bands emerged during the Estallido Social in Chile. In Aysén, there’s a band called Adokines that released a great album a couple of years ago, inspired by the 2012 social uprisings in the region. In Arica, there’s Niño Calavera, a band with a really strong sound — they’re located way up in the far north of the country, and they’re just as good as any professional band from Santiago. Everything they do is self-managed, which is incredibly valuable. These young musicians invest their own money and time into recording, performing well live, and producing really solid work. That last band, for example, uses its distance from Santiago to its advantage — they travel to Peru, where they are quite well known. There is a broad circuit of bands there. What’s cool is that larger bands often support the smaller ones, like BBS Paranoicos or Machuca, which are from Concepción. Things feel really decentralized now.

What is the significance of this decentralization? In addition to what you’ve already mentioned, how do you think Chile Punk can help bring visibility to these regional bands already connected to the rest of Chile but not based in Santiago?

I wouldn’t give all the credit to Chile Punk, as these individuals are quite adept at promoting themselves, but the page has certainly helped by serving as a showcase. It has become somewhat recognized within the Chilean punk-rock scene, and bands are very appreciative when they have the opportunity to share their music or promote a show. Thus, the page plays a role there, but much of the credit also goes to the musicians themselves and their self-managed efforts. It’s great that some of the bigger bands in this scene come from outside the capital — like Tetranarko, which is quite well-known in Santiago; Pegote from Concepción, who are incredibly friendly; Machuca, another major band in the scene…; Ocho Bolas from Valparaíso. As I mentioned, I find it really interesting to see such an even distribution across different regions. Chile is an extremely centralized country —economically, socially, and culturally. Much of the cultural funding is directed toward large cultural centers like GAM, which limits opportunities for grassroots cultural initiatives in other regions of the country. While there is some degree of decentralization, most major concerts still take place in Santiago. Nonetheless, the bands themselves have begun to shift this trend. There’s a musicologist named Jorge Canales who has appeared on the podcast several times. He studies the history of Chilean punk, and we’ve discussed how the movement started — but the focus is typically on Santiago because there is more documentation. Even so, Jorge acknowledges that initiatives were taking place in other regions as early as the 1980s; they just haven’t been widely discussed. I imagine there are people researching that now. Speaking of which, there’s a whole network of writers dedicated to rescuing and documenting stories about punk-rock through books. Several great books have been published by Santiago-Ander and the Camino publishing house — two independent publishers that have released truly fascinating titles about punk and music in general. This type of literature and independent publishing will undoubtedly aid the movement in reaching more people, expanding somewhat, and attracting greater attention. It helps individuals understand that this punk-rock scene exists — and that it’s not exclusive to those who dress in a particular style.

The book ¿Qué es el punk? 100 formas de entenderlo (What Is Punk? 100 Ways to Understand It) is available on the website of Santiago-Ander Publishing: See book

Do you think this visibility can also contribute to the creation of more spaces — something you mentioned earlier as a problem, the lack of spaces? Do you think this interdisciplinarity could help generate more spaces for punk bands?

I’d like to believe so. Recently, I was talking to a friend of mine who studied audiovisual communication about the possibility of doing a podcast episode on punk in film and video games. We often recall how, when we were kids, we played a Nintendo game where the antagonists were punks, and you had to fight them. In some late ‘80s movies, the criminals were portrayed as punks, and I think that image has been somewhat perpetuated. I know people who see a punk on the street and feel scared. Sometimes, these kids aren’t doing anything wrong. Sure, there are people who get into trouble, but a lot of times, it’s just a stereotype. Many people tell me there are venues that don’t want to rent out space because they fear things will get broken. And sometimes that happens; it’s true. Demystifying the idea of violent punk could be beneficial. Kids may act out for various reasons, but not solely due to their punk identity. Approaching this phenomenon from a multidisciplinary perspective might make a meaningful difference. Writers, researchers, journalists, and psychologists are studying this issue and discovering it involves more than just getting drunk or starting fights. There is much more beneath the surface. I believe that the visibility this multidisciplinary approach offers could help create more opportunities and dismantle the perception of these lost, intoxicated young people.

And to end the stereotypes…

Exactly. I hope so. I’m not sure what impact these publications have, but I believe there must be people who have accessed these books and realized that there’s much more behind the caricature of punk. For example, here in Germany, there are many spaces and more opportunities for bands. I think they experienced this 20 or 30 years ago. They already shattered those myths. Nowadays, seeing punks dressed in punk attire is like spotting an “endangered species.” If I see one on the street, it makes me happy! I’m not certain if anything remains of that, but I believe there’s still a lot of myth surrounding the archetypal figure of a punk.

Link to Chile Punk’s latest publication: Read more

I saw an announcement about moving forward with renewed energy for 2025. What have been the biggest challenges in maintaining an independent project over the years, and what strategies have you found useful to ensure continuity?

Yes, the page went on pause at the end of 2023. The truth is, it was due to a lack of time because I was involved with university work. For my friends in Chile — to whom I’ll send the link when this interview is published — we need to demystify what it means to live abroad. Immigrant life isn’t easy. Many people in Chile think that just because you live here, all your problems are solved. I’ve multiplied them! There’s a lack of time, and it’s hard to remain financially stable, as I haven’t found a balance that allows me to have free time to dedicate to the page. A significant difficulty has been the lack of collaborators. I can’t ask much from them because there’s no money involved. At one point, I tried telling them that if they were to write, I could pay them a little with the AFP retirement funds. I managed to pay a journalist for some articles, and the idea was for her to keep proposing topics, but in the end, she didn’t. People collaborate with good intentions, but not everyone has the time, and not everyone stays motivated to participate. That’s been tricky, and you can’t do everything alone. Sometimes, yes. There are days when I write an article, share two or three posts on social media, contact people, make time, and record a podcast episode. But it’s super difficult. Plus, the time difference complicates things. People tell me to meet at 10 PM in Chile, which would be 3 AM here. That’s a problem. I’ve tried to maintain continuity, especially on social media. Sometimes, when certain events happen, I attempt to have something prepared. I haven’t been very consistent, but what motivated me to return in 2025 was that people were still commenting on the podcast and social media. We recorded one last episode in 2023 when Mara Costa, the lead singer of BBS Paranoicos, passed away. It was a “tribute” episode, and we announced the closure. However, there were many comments like, “It’s a shame that it’s the last episode,” and, “I hope something can be done.” I’ve been thinking about it because you get attached to your projects. So much effort to just leave it as an archive on the internet. Therefore, as time allows, the goal is to be more active this year and keep going. When you self-manage your project, there’s a different connection because you have a product that you believe is amazing, and no one cares about it — the story of my journalistic life. Not long ago, I paid for an ad on Instagram to promote a post, and immediately, people started complaining that I had sold out to the system by giving my money to Facebook…

Wow, what a demanding audience!

It’s a tough audience, but the feedback from this group — which is more discerning than a general audience — is rewarding. Occasionally, insults appear as well. Initially, I took the hate messages very personally and chose not to respond. However, I actually receive more supportive messages than insults. The balance is favorable!

I know you play guitar — how did your interest in music begin? Additionally, how do you think it has influenced your career as a journalist and your work with Chile Punk?

There was always music at home. My mom and dad are musicians, so I grew up surrounded by it. In the final years of the dictatorship, we often listened to protest songs in our house. My mom nurtured this musical interest, and my father enrolled us in a conservatory at the University of Talca when we were kids. My older brother studied guitar, while my younger brother studied cello. The oldest pursued music fully — musicology, while the youngest played a lot of cello — he was very talented. I was the lazy one. I said I liked playing the violin but quit soon after. That musical interest went dormant until I discovered punk. At that time, my cousin — who’s also a contributor to the page — and my brother and I began playing punk music. I didn’t know how to play anything, so we went to a rehearsal without knowing how to play any instruments. The most punk thing ever! [laughs]. I grabbed a bass and just improvised, playing whatever notes came to mind. Each of us played something different. Over time, we learned to play on our own. I never really drifted away from music; it has always played an important role in my life. I can’t imagine my life without it, always present every day. I find it fascinating how we associate moments, places, and experiences with the music we were listening to at the time. Sometimes, I hear an album I haven’t listened to in a long time, and I get transported back to my life in 2014. It’s incredibly interesting and beautiful! That’s how I got into this music. It stuck; it wasn’t just a teenage phase. Although I’m still a teenager at 40! [laughs]. Professionally, I never really managed to link my studies with music. Toward the end of my time in Santiago, I worked as a music journalist for a newspaper called Hoy por Hoy. That was when I finally combined the two things I loved. I then began to shape the idea for this project, which made a lot of sense to me: connecting the music I’m passionate about with journalism. In some way, I’ve been able to reconnect with my profession — which I haven’t practiced in Germany. That’s the path I’ve followed with punk and journalism. Now, from punk, I carry a critical perspective on things. I worked at several fairly conservative newspapers in Chile, and I always maintained a critical stance toward what I was doing, even though I had no editorial decision-making power. Still, I realized that what I was doing felt contradictory. That connects with the path I’ve taken through punk and protest music.

Your subversive soul always found a way to reveal itself — especially while working at more conservative newspapers…

It was terrible! There were days I felt awful working for the empire [laughs]. I completed my internship at El Mercurio de Valparaíso, contributing to the sports section. One day, Agustín Edwards appeared. I was at the computer when the editor of the paper — who was always very kind to me — approached and said, “Let me introduce you to Felipe, a contributor.” I turned around and saw an elderly man who shook my hand. As I looked up, I realized it was Agustín Edwards. I’m not sure what expression I had, but afterward, my colleagues kept teasing me, saying he was going to fire me. It was terrible! Ironically, most of my professional life ended up being at El Mercurio. Later, I transferred to Las Últimas Noticias in Santiago. My dream was to work as a journalist there. After that, I had a brief stint at the Fundación Teatro a Mil, working in theater promotion, which was enjoyable. Then, I moved on to Hoy por Hoy, which is also a part of El Mercurio’s regional media. There was a contradiction between my worldview and what those newspapers represented. But I had to earn a living. I looked around and saw that most of my friends and colleagues were unemployed or stuck in badly paid jobs. I had stability on one hand, and many people gave me a hard time for it. Ultimately, all that experience in high-level, structured journalism has benefited Chile Punk, as the page presents itself as a project with original, thoughtful content, and it’s exceptionally well written. It’s a pleasure to read a well-crafted article!

How do you balance your news coverage in general? Do you favor in-depth or investigative content? Or do you draw from your own interests and then shape that into quality content?

One thing I value from my experience at those newspapers is their commitment to serious journalistic standards. I wouldn’t say that the journalists lied. Sure, there were biases, among other issues, but there was a dedication to facts. A news report, for example, had to include verifiable data, and we always had to adhere to that. If we conducted a phone interview, we always needed to have a backup of the conversation. I encountered a few tight spots at Las Últimas Noticias because people claimed more than once, “I didn’t say that.” Well, I had it recorded. In general, the work was carried out with solid standards — even if the content sometimes felt disposable, the work itself was professional. From Las Últimas Noticias, I really appreciated the writing style. They preferred storytelling over merely delivering hard news. Yes, they published some sensational pieces — like celebrity gossip — but if you actually read the paper, aside from the topics, it was often well-written. The people who work there write exceptionally well, and some are very talented. I learned a lot from that environment and tried to incorporate some of it into the project. I realized there wasn’t a space providing punk with high-quality content — and I don’t think it sounds pretentious to say that…

No, you’re just referring to a well-crafted, well-written text — one that has no spelling mistakes and features a clear narrative thread…

Exactly. If you start looking around, you’ll find many blogs run by hobbyists. There’s one particularly good blog that shares tons of bands — you can download music, and it’s super comprehensive — but it isn’t enjoyable to read. That might be our differentiating factor: applying professional knowledge to writing and storytelling to bring it into this world that’s often associated with sloppiness. I don’t know if everyone who reads it notices or appreciates that, but that’s what we wanted to achieve. We’re never going to publish something that someone could refute. We don’t want to spread fake news. We aim to be responsible and serious with the information — even when we’re discussing punk. A lot of people just rewrite and repost things without verifying, and that happens frequently in major media too. Due to a lack of resources, they buy pre-packaged news from agencies. The press no longer has correspondents, and many people have asked me: “Why don’t you work as a correspondent for Chile from Germany?” In this case, nobody’s interested, because the DPA (Deutsche Presse-Agentur — German Press Agency) sends out news, and newspapers pay a monthly fee to receive it. They purchase the finished stories — that’s why you’ll see the same DPA or Reuters (a UK-based news agency) article in La Tercera, El Mercurio, etc.

Now I understand why the same article can sometimes appear in different newspapers…

Exactly. It’s much cheaper for media outlets, but at the same time, it standardizes information. I find that dangerous because subjectivity plays an important role as well. Many people say journalists shouldn’t be subjective. On the contrary — I must be subjective. My life experiences shape how I see the world, and I need to be transparent about that. I express this in a text or a journalistic piece. People will judge whether they like it or not, but I believe it’s far more interesting than the homogenization of news. If you visit the international sections of newspapers, you’ll find the exact same story. It’s like paying for Netflix and getting a daily stream of international news. This whole model has harmed journalists — there’s less work.

Regarding the 2025 concert schedule in Chile, which events do you find particularly interesting or important as the platform’s editor?

Among the concerts happening in Chile, one that truly captures my attention is the April performance by Evaristo Páramo — a Spanish musician and the legendary frontman of La Polla Records, a band that has influenced countless others in this region. If you ask any punk music listener, they’ll tell you they know La Polla Records. This guy — I believe it was right during the pandemic when large events were still allowed — came to Chile with La Polla Records. They were scheduled to perform in a stadium, but the punks disrupted the concert. Those damn punks ruined punk! [laughs]. They wouldn’t let the band play, jumped on stage drunk to sing, and after three or four songs, the concert was halted. It wasn’t safe for anyone — neither the musicians nor the audience. Now, Evaristo is returning. I believe there are high expectations surrounding this concert since he’s such a legendary figure. That show will surely make a significant impact — if it actually occurs, of course. Check out the concert at the Estadio Municipal de La Florida. It was chaos. Seriously!

Link to the article published in La Tercera about the cancellation of La Polla Records’ show in Chile: «Crónica de un desastre: el suspendido concierto de La Polla Records en Chile»

Alright Felipe, the last two questions are the ones I always ask every interviewee. The first one is: what are your favorite music platforms for discovering new music or for keeping up with your all-time favorites?

I’m pretty basic — I stick to the classics. I use Spotify to listen to a lot of podcasts and music, and I also use YouTube. That’s where I discover and enjoy new bands. Honestly, to be completely transparent, I’ve found more bands because they’ve reached out to me through the project. I feel really nostalgic about the old days. I used to live in Talca, and discovering new music often depended on a friend returning from Santiago with a cassette. Some people didn’t even want to share their finds because they didn’t want everyone to hear the band they had just discovered. It was quite difficult. A friend would show up with a pirated tape that had more white noise than actual music. Looking back, it was fun [laughs]. We would always have side A filled with one band and side B with another. You’d make your own mixtapes — but that’s long gone now.

What is your favorite album, composer, singer, or musical piece? What is a song or piece you always listen to that transports you to a specific place?

It’s hard to pick just one because it goes in phases. The albums I always return to are London Calling by The Clash, La Voz de los 80 by Los Prisioneros, and a classical piece that I really like — even if it’s a bit of a cliché — Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. I love it. I know it by heart. I’ve listened to it thousands of times. There’s also a composer named Philip Glass whom I really admire. He has a modern opera called Einstein on the Beach that’s incredibly interesting. None of this is related to punk, but these are things I listen to regularly. I always come back to those albums. Sometimes a long time passes without listening to them at all, and other times I’m into different music — but I always return to them again and again.

You’re the first person to answer that question the way I would. I’m always surprised when people mention just one song or piece. I can’t respond that way because sometimes I’m listening to this, and other times to that…

Exactly! What’s your favorite song? Today, it might be this one — but tomorrow, it will be another. Musical taste isn’t static; it flows and changes constantly, depending on your mood. It’s always in motion.

I completely agree. Thank you very much for the interview and for sharing all your stories and details about your project, Chile Punk. I hope many more people discover the initiative.

Thank you for your time, for the invitation — I appreciate everything!

Deja un comentario