Maximiliano Soto, or simply Max for those of us who have known him for years, is making waves in the European composition scene. In September of this year, it was announced that he was the proud winner of the Busoni-Kompositionspreis 2024, a composition award granted every two to three years by the Akademie der Künste (Academy of Arts) in Berlin to young composers who are still unknown to the public. Max is the first Chilean and Latin American to receive this award, which will be presented to him in a ceremony to be held on November 30 at the Akademie der Künste, located at Pariser Platz. The Ensemble Mosaik will perform some of his works, as well as those of Aribert Reimann, who passed away in 2024, and Ferruccio Busoni, who named the award.

I met Max through my clarinetist friend Rodrigo, when we were studying at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Chile. Max has always had a unique personality, and I remember seeing him often immersed in the complex inner world of a composer. Max lived near my house, and sometimes the three of us would go for pizza at RomaAmoR pizzeria, a nearby family-run place. Rodrigo and Max loved their Roman-style pizza! Many years later, we met again in the city of Freiburg, where Max showed me a bit of the city, as well as the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, the place where he was doing his Konzertexamen, a postgraduate degree after the master’s degree.

Along with the Busoni Award, Max was also the winner of the Call For Scored EstOvest Festival 2024 in tribute to the celebrated Italian composer Luigi Nono. Max was in Italy this month for the premiere of his work Disparate.

Screenshots taken from the EstOvest Festival 2024 program. The full program and the news published in July of this year are available online.

Max is currently living as a composition grant holder at the Künstlerdorf Schöpingen Foundation in the city of Münster, a residency that lasts four months. Before starting the interview, he told me that three composers are awarded scholarships each year, and the rest are approximately 20-25 people, including poets, playwrights, film librettists, visual artists, among many others.

Is this a place where one should go to create, away from all other distractions and focus one’s attention on creation?

Yes, yes. The objective is to meet, to get to know many people from other places. The people in charge make sure it is intergenerational, so there are also people who are finishing their careers, others who are writing their first book, things like that. I joked that it has like the structure of a psychiatric hospital, of a Pflegeheim, but it’s like the artist’s version. It has the same structure…I can feel at home really, because I can joke with people and not feel strange. For example, among my colleagues, not many know the poet Barbara Küller, of whom I’ve done two musical theaters. And here, there was a guy who was a filmmaker and had been a student of hers. Or, for example, with the sculptors, we imagine building new instruments, ceramic giants […]. A writer arrived from Iran who had recently been imprisoned because one of his publications had not been registered with the Ministry of Culture. He was in Slovakia and now he came here. And, of course, I’m learning a bit of Persian, a bit of Greek, sharing films, the creative process, going to the Contemporary Music Festival in Münster, and so on.

And how does the residency end? Does it end in a concert?

No, not at all. It’s very similar to that contract Beethoven had, in which it said, «we’re going to pay you even if you don’t do anything.»

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself, your academic life and how you got here?

Well, after finishing my studies in Santiago, I got the Carlos Riesco Academy of Fine Arts Composition Prize in 2016. And with that money, then with my wife we sold everything and came to Europe because she has European nationality. We arrived in Freiburg where I studied for 5 years, master and then Konzertexamen and I graduated in 2022. Immediately after that, I have lived as a freelance composer and copyist. I have won many prizes, two premieres with the SWR Symphonieorchester, and now the Berlin Academy of Arts prize. I finished my studies in Chile with the composition prize there and in Germany with the Berlin Academy prize.

They have been two emblematic cycle closures, haven’t they?

Yes, yes, definitely.

Are you working on anything new? What projects do you have in mind?

Right now, I’m finishing my project here at the Schöpingen Foundation, where I’m composing a 30-40 minute piano piece. Then, in 2025, I will dive into composing a piece for the Abeceda Festival in Slovenia, who invited me for the third year as composer in residence. I also got a scholarship from the Hoyter Academy of Theatrical Music of the Deutsche Bank, for which I will compose an opera to be premiered on October 30, 2026.

You never stop. You go from project to project!

Yes, that’s not the problem. The problem is making ends meet, but with confidence and luck I haven’t had any problems in the last few years. You need luck above all to be healthy, not to fall into illness, poverty or war. One of the biggest challenges in the European scene in general is the importance of a network. You always need someone to act as a «midwife» to help you reach out to a group. When I came to Germany, my composition teacher had a super important task: to introduce me. It was only through networking, for example, that I wrote for the Landesjugendensemble, having just arrived in Germany. Then I was introduced to Frank Kämpfer, Editor and Producer of Contemporary Music and also Artistic Director of the Deutschlandfunk Contemporary Music Forum. That was in 2018 and in 2021, only three years later, I received a commission from them. Likewise, the person who nominated me from the Berlin Academy knew me. That’s why he recommended me.

In the end, it’s like in any job, where networks end up playing a crucial role…

Yes. On the one hand, there is luck, and on the other hand the fruit of non-stop and unpaid work, thanks to which I have the composition awards that are anonymous or where there are people on the jury who don’t necessarily know me. Of course, I have colleagues of my generation who do not go to competitions and, only by taking care of their networks, get commissions for operas, for festivals like Donaueschinger, etc. In that sense, I’m kind of in the minor leagues and the Berlin Academy prize tries to moderate that somehow. They nominate composers who should be a little bit better known. But after that prize it’s not like somebody comes knocking on your door or calls you on the phone and says, “I want to commission a piece.” It’s just a help.

What would you recommend to someone interested in composition, whether as an amateur or a professional? Is there any advice you would give to young composers starting their careers?

When I arrived in Germany, I didn’t know anyone… I don’t remember exactly how it happened; I’m not sure if I read a poem or had a dream where there were spiders. Especially at the beginning, I interpreted that as a sign that I had to be like a spider in the sense that I needed to position myself in the small corner of my desk where I worked, and since I didn’t have the resources to leave that spot, I decided to work like a spider that slowly weaves a web. Then, I would listen, and when an insect fell into the web, I would try to catch it. That was my way of working for five or six years; waiting for the food to somehow fall into my plate, but the web had to be made. And only now, after winning several scholarships and awards and achieving some financial stability, I could leave Freiburg and move around more, to seek opportunities. It’s not enough to just send an email; you have to be there. At least, that’s the culture in Germany and in Europe in general. As a second piece of advice for young people in Chile, it’s necessary to first overcome the lack of understanding from family, who rarely envision a career in composition. After years of suggestions to change professions, the best advice I received was from my grandfather, who, in a serious tone, said to me, «I, who have done nothing but foolish things in my life, what advice can I give you?» In a society where we suffer to not be unwell, instead of aspiring to be well, the desire to live a simple and free life to create is seen as strange and undesirable. Being a musician means not only following a passion but also transforming others’ expectations into your own dream.

How would you describe your evolution as a composer in recent years?

Through the spider analogy. I’ve been writing chamber music like crazy for fifteen years. The other day I counted, and just since 2017, I have over fifty works premiered. This means, I am one of the most prolific people in the country, with works that do not repeat themselves. Even so, I haven’t been able to move beyond small chamber music for one to ten people, and what I want is to write for groups of twenty musicians—large ensembles—where I can test the space, have access to a big hall, take it to the streets, and create works for an entire city. But I can’t, because I don’t have the necessary contacts to gain the trust that, for example, someone like Stockhausen had. I am against any form of thinking that suggests there is an evolution in a composer’s work. I don’t consider my work to be much more evolved than when I was 19 years old. Rather, the circumstances change. More than an evolution, my work is a series of errors that occur one after the other, and I believe that is a common denominator for everyone in science, medicine, the arts, etc. It’s about having the opportunity to make the right mistake. The privilege of having someone trust you and give you the space to make mistakes is the only way to evolve your own language.

Do you mean that there is no upward or downward evolution, and that the process should be described in another way? Still, in this series of mistakes you mentioned, there seems to be a forward movement, don’t you think?

For example, when people were making cheese, and all of a sudden a Frenchman made a mistake and created blue mold cheese. One could say that was a serious mistake because he lost the entire production. But later, they realized it wasn’t. Now, blue cheese is considered an art form. The same goes for champagne. There was a mistake in the production of the wine, and it became fizzy. Now, we view that mistake as the basis for a whole new technique. Music, in a way, is also a little bit like that. I would dare to generalize that this applies to art and science. So, when I compose a new work, I always make sure to leave at least a little space where I don’t really know what I’m doing. In a controlled environment, where I understand how it’s progressing, there is always a detail that I know I don’t understand well. Leaving that space open and undefined allows me to see how the performer reacts, and if it works well, I’m left with an idea for the next piece. But it takes luck.

In what sense?

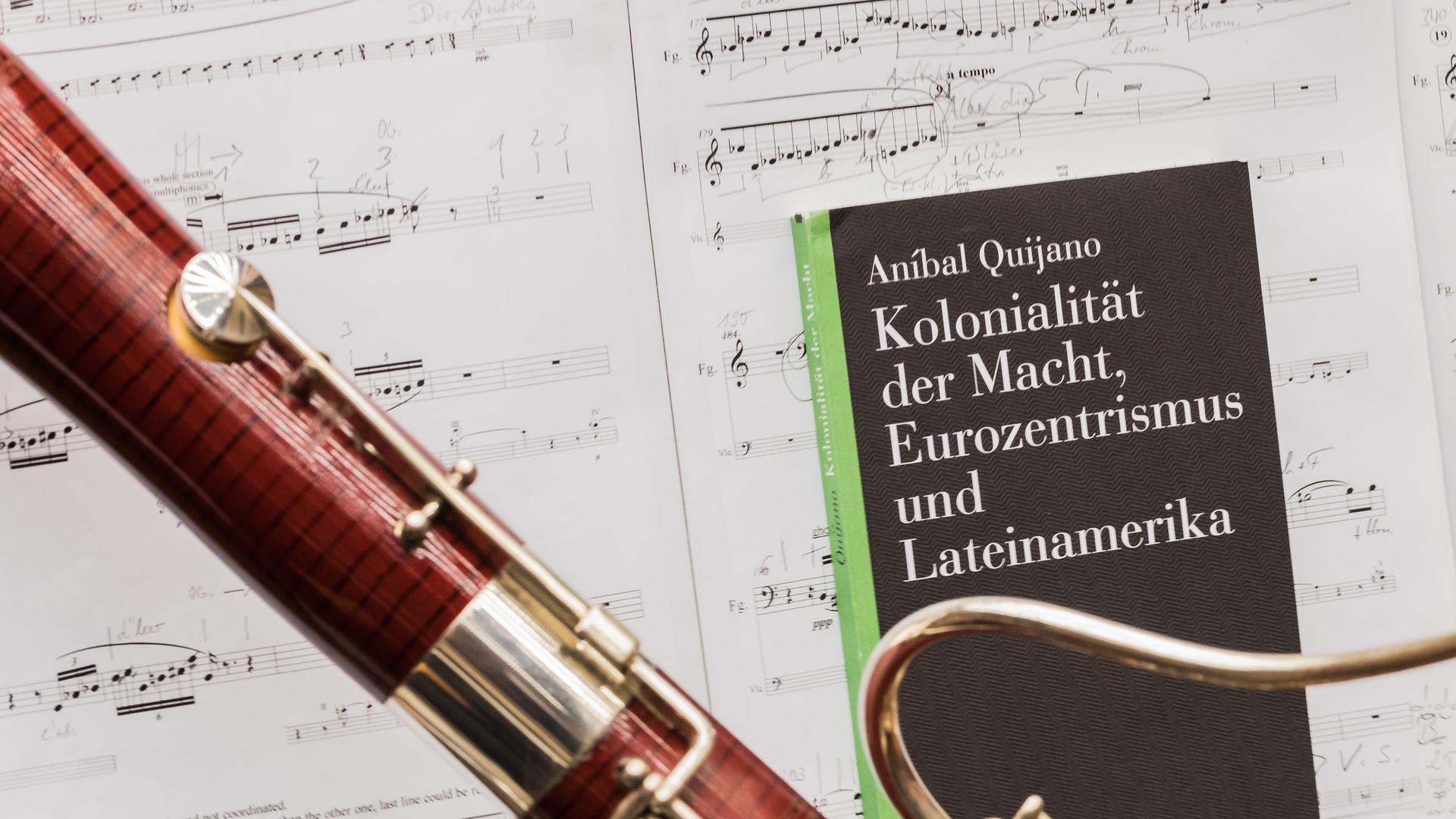

When I was a kid, back in Santiago, I worked a lot with harmonics—harmonics on strings, etc. Since I didn’t have performers with experience in that area, I spent about five or six years thinking there were things that simply couldn’t be done. But when I arrived in Germany, half an hour from Freiburg is Basel, and there I had the fortune to work with a cellist named Ellen Fallowfield in 2022 with the Aventure Ensemble. She dedicated her doctoral research solely to the production of harmonics and multiharmonics on strings, particularly the cello. After that experience, I learned how to explain it, so when someone said it couldn’t be done, I could now tell them, «Look, this is how it’s done.» Thanks to my encounter with Fallowfield, I created a study, but not for cello; instead, it was for solo viola because a violist had promised me that if I wrote whatever I wanted, he would play it. I spent a year writing a piece for solo viola, a study on harmonics, lasting only about 8 minutes. Additionally, I was working on a larger project for the Deutschlandfunk. Well, I finished that piece for solo viola, but it wasn’t played. The large ensemble piece premiered at Deutschlandfunk, and I had to wait another year before the violist who had promised to play my work finally told me he couldn’t do it for less than 2,000 euros, since it was a piece that he needed two or three months to prepare well. After searching for other violists to play it, everyone told me no, and in an act of immense hatred and revenge, I transposed the piece down an octave and changed the clef to bass. In less than three months, I found someone who premiered the work, this time for solo cello. Four years have passed, and the piece has been performed three or four times, and now it’s going to be premiered in Chile and Germany.

So, does your creative process arise more from interactions with other people who commission you, or do you sometimes feel inclined to write certain types of compositions?

A very particular example is a collaboration I recently did with Coco Lau, a soprano from Hong Kong and Berlin. I had just finished a musical theater piece with a group from Freiburg, and with the video in hand, I started weaving a web like spiders do. I reached out to people who worked in musical theater, and Coco Lau responded. She told me she wanted to work on new pieces, but she was doing a specific project focused on the image of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene. She said, «Do whatever you want, but it has to be within this constraint.» This piece is set to premiere on December 3 at the Haus für Poesie. Well, using this example, it’s quite similar to what happens when you are given an orchestra or an ensemble. They say, «We want to work with you, but this is the venue and these are the instruments.» However, the agency you have as a composer lies in all the things they don’t tell you. Yes, they can specify ten minutes and these instruments, but they don’t discuss anything else. The soprano told me it had to be about the Virgin Mary and for solo soprano, but nothing regarding the duration. I ended up creating a long piece of 20 minutes with masks, because we didn’t discuss costumes or texts. In reality, the composer adapts to a lot of things that perhaps many people aren’t aware of.

You can compose whatever you want without limits, but there are indeed certain boundaries and limitations from the performers, like in the case of the viola you were telling me about…

Yes, yes, before working with the instrument, one works with people. Depending on who you are collaborating with, that will define the space and the audience you are reaching, which is an important factor. Personally, I always think, «What do these people imagine? Why are they coming to the concert? Are they paying for a ticket or not? Are they coming because they want to, or are they being brought along? What programs have been done before that these people applaud?» In the piece commissioned by Deutschlandfunk, I was considering creating a very calm piece where almost nothing happened, let’s say. One day, a musician from the group who had nothing to do with the commission approached me and said, «Oh, how beautiful! I love finally having a piece that is deeply Chilean!» That made me reflect on the question, «What is ‘Chilean’ exactly?» There is a whole series of things that cannot be well described.

But was that piece for the Deutschlandfunk a “Chilean” work for you, or was that just the musician’s perception?

No, I hadn’t even written it yet! I was thinking of calling it Cyanotype, which has nothing to do with that.

So, he mentioned it as a “Chilean” work assuming that, since you’re Chilean, you were going to compose something Chilean…

Yes, and that short-circuited something in me. I felt a very deep resentment, and I tried to put that into the score. I composed a piece that’s the most tangled and complex I’ve done so far…

Was that because you wanted to reflect some part of your experience?

No, I got really irritated and thought, “I’m going to write something so difficult that this guy will regret it.” I wanted to see him sweat!

Is this just an anecdote, or are you telling me this because it’s been a pivotal moment in your career as a composer? I mean the “short circuit” moment…

This is important because it shows a creative solution I wouldn’t have reached if it weren’t for the drive that came from that frustration. This piece matters because it was the first commission I received after finishing my studies, and I tested everything I’d learned in that score. It’s more of an exploration of serialist thought and tonal music practices. It’s going to be performed again now in Berlin for the award ceremony, so I made a new, revised version that’s a bit simpler.

Among all the pieces you’ve composed, is this one special to you?

Yes, definitely. Out of all the pieces I’ve done, many of them, since they’re unpaid, I have to compose in my free time, so when I hand them in, I’m not fully satisfied with the result. But with Cyanotype, I was thinking about it and working on it every day for two years, and even now, two years after finishing it, I’m still revising it. When I went to Chile, I showed this score to students at the University of Chile, and I was struck by their reactions to a small section where a performer played percussion with spoons. One student said, “Oh, but that’s typical of Chile! The spoons in the cueca…” And others said, “It sounds like the city of Santiago!” After that, I thought maybe my audience was a Santiago audience without me even knowing it. The piece was written for an audience that didn’t exist when it was performed.

The work Cyanotypie (2022) was a composition commissioned by Deutschlandfunk and funded by the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation. You can listen to Ensemble Aventure’s performance here.

*Photo taken from the Deutschlandfunk website: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/musik-panorama-108.html

Speaking of your important works, I assume that Roto is also in that group…

Yes, it’s like an orchestral version of Cyanotype. I titled it Roto because when I finished it, it coincided with the 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile. Roto is a reference to my last name, Soto, which is as “roto” as it gets. In a way, if you look at the last names of composers in Chile, they’re rarely names like Soto or Rojas or Mapuche names. I also remembered a professor at the University of Chile who once walked in on a student rehearsal where they were playing Mozart and said, “Ah, the rotitos playing Mozart!” This hit my classmates deeply, and they never forgot it—they would repeat it every year. It was like a scar that stayed with them.

Definitions of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) on the word Roto, ta:

- adj. Ragged and wearing torn clothing. Synonyms: ragged, frayed, scruffy, tattered, shabby.

- colloq. noun. Chile & Mex. A person who is rude or has coarse manners.

Wait, is this true?

Yes, yes, yes! When that professor said it, it really hurt my classmates. One of them had a friend who bought a bassoon with money his grandmother got from selling her house; she sold it just to give him the funds. These were people who had really worked hard to get there. Now, for once, the roles are reversed, and there’s a rotito writing for the Stuttgart Symphony Orchestra. Maybe performing this piece in Chile someday would hold even more significance, I think. Every year, I reach out at least twice to various Chilean orchestras about working together. I’ve written to the Chamber Orchestra of Chile, the USACH Orchestra, the Chilean Symphony Orchestra, but they don’t even respond to my emails.

Max, we’re coming back to the initial topic from before the interview—that in Chile, they always play the same things with the same performers…

Yes, new things do happen in Chile, but there’s an elite group that’s always involved. When Pinochet took power after the military coup, that very year theater was made illegal for a year, and the composition degree was shut down. One of the first things they prohibited was our work, and I think that left a mark that is only just beginning to improve.

Max, tell me about the process of working with SWR, was it also collaborative?

Yes, we had more rehearsals than a professional composer would normally have. The orchestra was also a mixed grouping between professionals and students. In that sense, it’s very rich work, it’s a gigantic investment to make. I don’t want to know how much a minute of orchestra costs but the calculation can be made. For that reason, what they emphasize the most is the importance of expressing yourself briefly to answer the orchestra’s doubts. If they ask you how to do an effect, you have to know how to say it in 5 or 6 words because one minute is already too much.

Did it take a lot out of you to do it?

It was my second piece being performed, so by then, I already knew what to expect. The first time was very challenging because I had no idea. I was shaking as I walked on stage! The conductor, Titus Engel, would ask us, “Do you like how it sounds?” And I’d reply, “Well, it has to be loud, but not too loud… imagine this story when I was 5 years old, and my mom and dad told me…” And they’d stop me there and ask, “Louder or softer?” I’d say, “I don’t know, how would I know?” In the end, the conductor had to spend at least an hour with me and the other students, explaining how to communicate. He’d say, “Just say the first thing that comes to mind in one or two words. If you don’t like it, then tell them to do the opposite.” They even had to teach us how to walk up the stairs, shake hands with the concertmaster first, then the conductor, and that was it. It was such a privilege! One time, after a rehearsal, the conductor stayed with me for three hours, going through the orchestration bar by bar. Afterward, he handed me a pencil, and I had to go stand by stand, making changes. The second time I went, I was much better prepared. The orchestration had no mistakes, just one coordination issue with the trombones. I’d given them a glissando while they also had to move the mute, so they looked like clowns. Also, this was a piece where I used spatialization as a compositional technique. There were lines that crossed the stage space, but for it to work, we needed a concert hall where you could really feel the space — ideally, a stage at least 600 meters long…

But were you satisfied with the result?

No, that’s why I made another one! [Laughs].

What has winning the Busoni Prize this year meant to you? Is there a “before and after” for your career?

With this prize? I don’t know, maybe there won’t be an «after.» It depends on what happens to me, because let’s suppose I stop composing today and never write again, or I keep writing but only poor-quality works. In that case, the prize wouldn’t mean much. But if I manage to write at least one piece that’s worth something, that’s worth my memory, then yes, it does. It’s a bit ironic because it’s dedicated to composers who aren’t well-known. It’s like a consolation prize! [Laughs] It’s a process of healing the story of Chilean composers who disappeared and now show up elsewhere, but not in Chile.

It’s like the saying that no one is a prophet in their own land, right?

Mmm, I don’t like that saying because there are people who are prophets in their own land. We have plenty of them in Chile, who live peacefully in their little homes, compose each year, and get paid well. They might not be recognized elsewhere, but they are at home. I think the people who truly do important things are the ones who rarely, or almost never, get recognized in Chile. On the other hand, people who are kind of mediocre do carve out a niche because they’re more focused on recognition, too. Look, the most gratifying thing about being a composer for me, the moment when I most feel like a human being, is when I’m deep in the work, composing a piece that makes me forget to eat, to sleep, to take care of myself. Just working to create that piece in that moment. When I can forget all society’s demands and work in peace, that’s when I feel most free—not happier, but free and filled with a desire to live. My desire for recognition, my work frustrations, my social awkwardness, the need for money, and all the disgusting needs of any human being are the least important to me. When I feel most like myself is in that moment of composing and working. That is a privilege—the greatest privilege of all!

How has the reception of your work been in Europe, and how would you compare it with the reception you received in Chile?

I don’t know; it’s hard to say. When I lived in Chile, it’s important to mention that there was an orchestra that performed all the pieces I wrote for them, the Marga Marga Orchestra, which gave me access to practice with strings, something I didn’t have in any other moment of my life. They had an open competition where, obviously, I composed for free. It wasn’t a workshop or anything, but the premise was that the pieces submitted would be performed, regardless of whether they won the final prize or not. That was a very important opportunity. The other was my work for almost 5 or 6 years with Germina.Cciones Chile, an NGO with which we held workshops for young people, through which I had about 10 more premieres for chamber music. I worked with the ensemble from the Instituto Professional Projazz, where we organized improvisation workshops with the Symphony Orchestra from El Bosque. There were a lot of things where I always felt that the audience was very grateful and happy to receive those works. While they weren’t the stages I wanted to reach, they were the stages where my music was well received. Additionally, the Marga Marga Orchestra took these pieces to different towns, so I always had a good reception from the audience. I believe the problem lies in the filter that exists beforehand, meaning the institution.

Of course, that’s exactly what I was going to say. I also remember when I gave concerts in Chile, the reception was always very good. A lot of people would come, and they always left very happy and grateful, but to organize a concert, you had to insist a lot…

Yes, and waste time. Honestly, I didn’t want to come to Europe. After finishing university, I put in a lot of effort—almost two years dedicated solely to organizing concerts, and those efforts, in the end, I don’t know if they were in vain, but they didn’t lead to anything. I tried to set up a series of concerts in the sixth region with no success, not because the audience didn’t want it, but because the people in charge didn’t see the value in it. In contrast, in Germany, the institution has interest, but I don’t know if the audience does. Where I did have a lot of success with the performers was in Slovenia. I was fortunate to be part of a group called the Abeceda Institute for Research in Art, Critical Thought, and Philosophy, with which I worked on a course they held in 2020. In 2022, they invited me as a composer in residence. The artistic director followed my career for a few years, and when they had the chance, they invited me back. This is the third consecutive year that I write four works for them. They premiered my piece for cello that I mentioned before, but I believe the audience isn’t always «there»… I am sure that my work is made for a Santiago audience, from downtown Santiago, but oh well. About three years ago, I decided to completely set aside cultural management. Perhaps it’s worth mentioning that when I arrived in Germany, I still continued with the practice I had in Chile of doing cultural management, and I organized some concerts of Chilean music at the University of Freiburg. We held one of the first concerts in honor of the composer Leni Alexander in Freiburg, alongside the Gender Equality Commission, of which I was a student representative for two years. Later, I founded a group called Compass Ensemble. However, after graduating, I decided to abandon management and dedicate myself to composing. In addition, I work as a copyist and assistant to others and as a score editor, along with the awards, commissions, and scholarships.

Do you think that Chilean institutions offer enough support to young composers and musicians? Are there platforms that could improve the visibility of Chilean composers abroad?

In Chile, the resources are there because there are state orchestras. What I would do is allow composers, regardless of their technical level, to submit their works to a center that is in charge of the country’s orchestras, for example, at the Ministry of Culture. Depending on their level or years of experience, they would enter a waiting list where they would be given a date for the premiere of their work. This way, orchestras would be required to dedicate at least 25% of their repertoire to a piece from this new archive that would be created. Another thing I would do is change the focus of the national music awards that reward merit. You cannot reward merit if we are not constantly investing in the creation of repertoires. I would abolish the national music award and use that money to fund, at least on a yearly basis, the creation of works. Look, this year the national music award was valued at 23 million Chilean pesos plus a lifetime pension of 20 UTM. With that, we could commission a significant number of pieces. Thus, in 10 years, we would generate many new works and create a market that could also be exported. We would have a repertoire of 200 symphonic orchestra or chamber ensemble scores that could be published in the music archive and performed around the world. It’s not difficult. The resources are there, and the composers are there. I would do that first, and then create a collaboration based on a network of orchestras in Latin America. It wouldn’t cost anything. It would be like, “I’ll send you this piece, and you send me that one; I’ll premiere it there, and you’ll premiere it here.” It’s not an additional expense; it’s just about rethinking how we perceive merit.

How do you see the future of composition?

You can’t know. Take Iran as an example; if we compare Chile and Iran in the 1950s, we are more or less at the same level. A nation with hundreds of composers and a culture that is thousands of years old. And today, their artists are in prison or live in the diaspora, as refugees. Today, we might be fine, but in two years, you could be imprisoned for being a woman, for example.

To finish, what are your favorite music platforms?

Live concerts; to attend one, you have to make the decision to go. When you buy a CD, you must take the risk of acquiring something whose sound you don’t know completely. That creates a dialogue. Spotify gives you a personalized selection in advance, which eliminates that minimal dialogue. I like YouTube and SoundCloud to showcase my work, but only as a reflection of a space that doesn’t exist on other platforms. I would like my works to be in concert halls, on records, and in archives.

Can you name your favorite album, composer, or musical piece? It can be classical or popular…

I had thought of Kaija Saariaho’s violin concerto. It’s not my favorite work, but I remember once going to the Feria del Disco in Santiago and finding that CD; at that moment, I thought, “Saariaho, what a strange name!” Then I played it on the radio, and I didn’t understand what I was listening to. I was about 14 years old. Additionally, Saariaho was one of the first pioneering composers of electronic music and studied and lived in Freiburg, which is the city where I live. I think Saariaho is one of the best composers out there and, maybe just because she’s a woman, she’s not on the lists. Listen to all her work; it’s impressive!

Thank you so much for your time to do this interview!

Thank you very much!

Deja un comentario