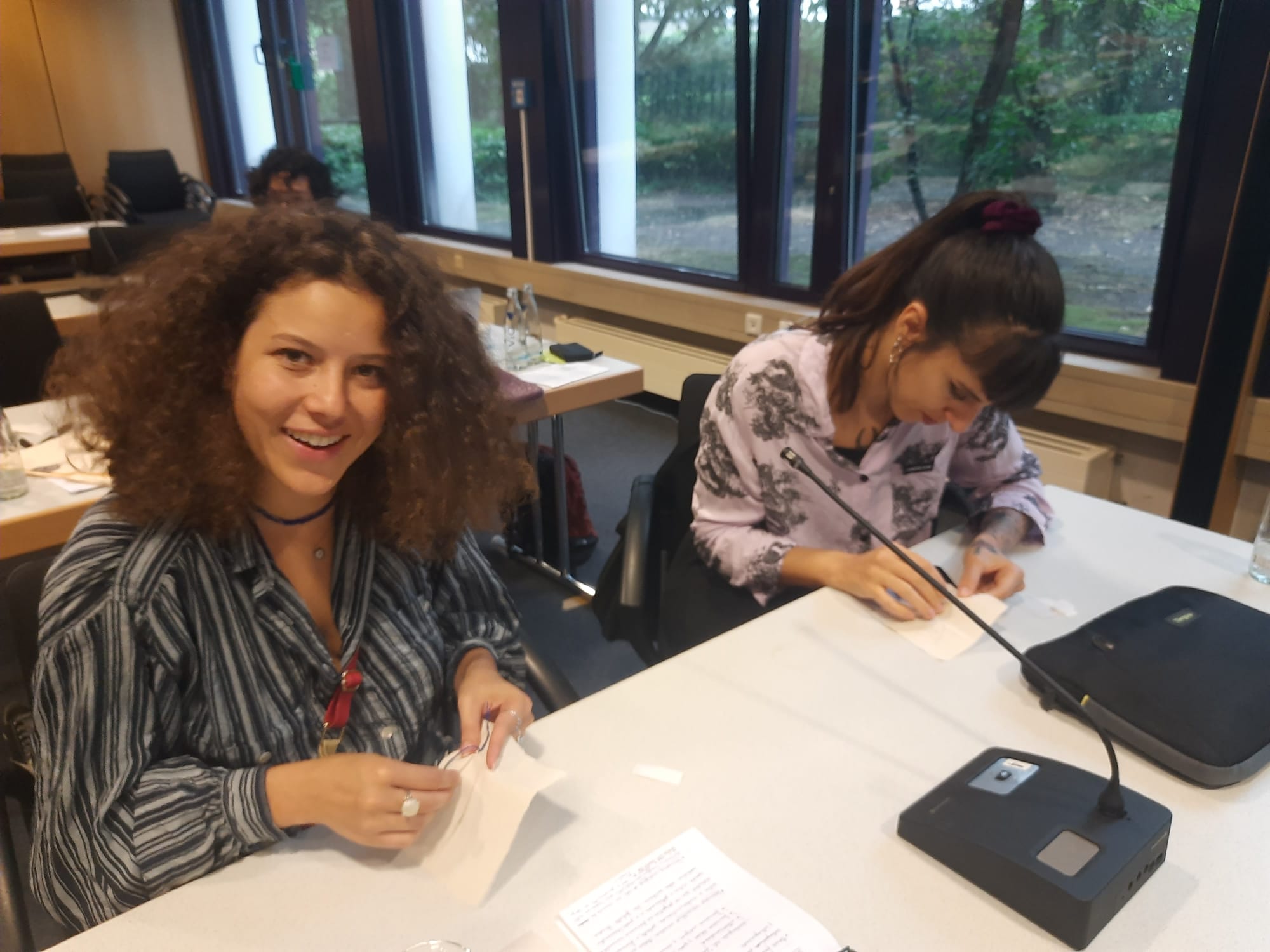

In July 2023 I had the opportunity to attend an event organized by the ILZ- Interdisziplinäres Lateinamerika Zentrum (Interdisciplinary Center for Latin American Studies), an organization for Latin American researchers at the University of Bonn. The third edition of the summer school, entitled “Nuevos feminismos en América Latina» (New Feminisms in Latin America), immediately caught my interest when I read the application form. During that semester, I had taken classes related to feminism and gender studies in my current master’s program in anthropology. I decided to apply and was accepted, along with a group of about 20 students from Latin America and Europe, most of whom came specifically for this occasion. The workshop lasted five intensive days during the third week of July, plus some other online meetings before and after the activity.

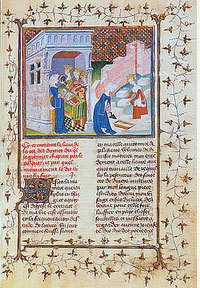

The program of the event covered a number of topics related to feminism, which were divided into four groups: 1) Contemporary feminist theories and delimitations of neighboring movements; 2) Intersectionality; 3) Breaking with modes of domination and its reproduction; 4) New cultural productions and representations. All participants could choose their group of preference and I, of course, chose group four, since, despite not being an expert on the subject, I am familiar with feminist cultural and artistic representations. Thus, the first day of the summer school featured presentations by professors and researchers whose areas of research focus on feminism. One that particularly interested me was that of Prof. Dr. Michael Schulz entitled “History of Feminist Philosophy”. Prof. Schulz, who teaches philosophy and theology at the University of Bonn, gave an interesting talk in which he recapitulated the history of women who, despite gender restrictions, challenged the social roles of their times by writing and publishing their works and observations. Among those I knew was the poet Christine de Pizan (1364-ca.1431), a humanist and poet of the Middle Ages born in Venice, but raised in France. She is the author of the famous book Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Women), a book considered a precursor of modern feminism, as it stood as a response to the criticisms of women at the time and defended their abilities in a completely patriarchal society. Christine de Pizan firmly believed that women had the same intellectual abilities as men and therefore advocated for their access to education, and through this allegory she described a city where women were honored and respected.

First page of Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, 1405.

National Library of France, Department of Manuscripts.

© cliché BNF

The final goal of the summer school each year was the publication of a compendium of articles written by the participants around the main theme. Each working group had a researcher in charge of guiding us through the process of drafting and developing a proposal to be submitted to the editors. My initial proposal and subsequent article revolved around music in the context of Latin American feminist protests. To narrow the topic, I chose three feminist movements that impacted beyond expectations. The first was the NiUnaMenos movement in Argentina, the second was the performance «Un violador en tu camino» by the Chilean collective LASTESIS and the last was Vivir Quintana’s “Canción sin miedo” in Mexico. The reasons for this selection were based not only on the international scope of these movements, but also on the diversity of the music in the three cases. NiUnaMenos used simple batucadas and simple chants, LASTESIS composed almost a protest anthem and «Canción sin Miedo» is already a much more elaborate composition, with complex accompaniment and harmonies. I finished writing the article in November 2023 and, after its last edition, it was published in May of this year. In it, I make a much more complete analysis of the music mentioned and also explore in depth the role of music in these Latin American movements.

Despite being a completely new topic for me, my lack of knowledge was not a barrier, as I was able to do enough research to develop a short thesis for my paper. Due to my doctorate, I already had a vast knowledge on the subject of music and protest, because during my first years at the University of Cologne, I was able to attend several courses with Prof. Federico Spinetti, a musicologist specialized in the subject and who has also been one of the best teachers I have had in my academic life, not only for his passion for teaching, but also for his dedication and desire that each student develops their potential in the best way. Spinetti let us venture into any subject we wanted, which meant that in class we were able to cover topics ranging from classical music, folk music to pop or heavy metal. Thanks to this, I already had a great understanding of the dialogue between music and social movements. In addition, the workshop provided me with the necessary context and theoretical framework to prepare the article, as well as a more than appropriate bibliography.

Delving into feminism and its many intersectionalities awakened in me an enormous curiosity, especially when listening to the presentations of my other colleagues, who covered topics such as feminism and indigenous peoples or feminism in literature. It is in the latter area that my venture into feminism began. The Encyclopedia Britannica defines feminism as «the belief in social, economic, and political equality of the sexes» and, by reading authors such as Silvia Federici or Rita Segato, I began to understand that gender problems in Latin American societies begin with the naturalization of violence (Federici 20181; Segato 20182). Silvia Federici’s perspectives on the normalization of certain female tasks and behaviors for the purpose of disciplining women and Rita Segato’s perspectives on the legitimization of gender violence and rape have marked a significant turning point in the way feminism is approached. These perspectives have not only enriched and broadened our understanding of feminist struggle, but have also brought critical dimensions by exploring its intersectionality with music in the framework of feminist activism.

Although my text only focused on feminism in Latin America, music and feminism have been present all over the world throughout the years. It should be made clear that feminist music does not have to be limited to protest music. In mainstream music, there are several songs containing feminist themes that have not been exempt from criticism and controversy. Recently, singer Miley Cyrus elevated women’s independence and self-reliance in her song Flowers, which became an anthem of freedom and empowerment for many women around the world and even had a cross-generational reach. By focusing on women not needing a man to be complete, this song proved to be a commercial success and ended up awarding Cyrus her first Grammy for Song of the Year in 2024.

But it can’t all be about music from the West. Several Muslim artists have also dabbled in feminism in recent years. This nomenclature is perhaps unthinkable to many, but there are several popular female singers who defy their gender roles, even in a field as defined as it is in the Muslim religion. Muslim singer Mona Haydar, a Syrian-American rapper, singer, poet and activist, became globally known when her song Hijabi (Wrap My Hijab) went viral in 2017. This song even made Billboard music magazine’s top 20 protest songs list that year. When I heard this song and saw the video clip, it made a huge impact on me, as I had never seen a female rapper wearing a hijab and I had never taken a look at things from the perspective of a Muslim woman who must overcome the many forms of discrimination for wearing a hijab in the West. The struggle of Muslim women is perhaps difficult for Westerners to understand, however, we must keep in mind that each culture and religion has its own specific concerns and contexts that influence gender dynamics and social roles. Muslim women often face a complex intersection of religious, cultural, social and political factors that shape their daily experiences and challenges.

Most Muslim women struggle for equal rights within their communities, confronting conservative interpretations of Islamic law that, in many cases, are not intrinsic to Islam, but are the result of patriarchal traditions and systems that use religion to justify discrimination. For Muslim women who find in their faith a source of strength and empowerment, Islam is not a barrier, but a platform from which they advocate for their rights and dignity. Examples of this can be seen in activists, academics and community leaders who work tirelessly for social justice and gender equity. In the musical realm, it seems to me that Mona Haydar has transcended many barriers by rapping in the first place, rapping with hijab and adding hip-hop elements in her music videos, as we must keep in mind that rap and hip-hop are two musical genres that have historically been attributed to men. In any case, we must not forget that Mona Haydar resides in the United States and therefore has complete freedom of expression through music. This is a privilege that many Muslim women residing in the Middle East do not have. Therefore, it is important to recognize the different realities and contexts in which Muslim women find themselves around the world.

In conclusion, feminism and music are a multilateral confluence that allows the flow of ideas and facilitates activism in any context. Contrary to what many think, feminism is not always associated with street protest, but with resistance, which can take many forms depending on the environment in which it develops. As Christine de Pizan put it in her book more than half a millennium ago, all women struggle against some form of oppression linked to the disdain that comes with being considered the “weaker sex”. Western women, especially Latin American women, struggle against unconscionable physical violence, which culminates in femicide, as I discussed in my article. On the other hand, Muslim women face the challenge of establishing their rights within a religious life that is often confused with cultural preferences, and which varies depending on the environment. For all of the above, it is crucial to recognize that feminism can manifest itself in different shapes, colors and sounds, and it is essential to respect each woman’s unique struggle. Each cultural and social context brings a different perspective to this struggle, which enriches the global feminist movement. Respecting and supporting these diverse manifestations of resistance not only strengthens the common cause, but also fosters deeper understanding and greater solidarity among women from different parts of the world.

Deja un comentario